Writing Variations for The Gown Made

08 Feb 2022

A couple months ago I was very honoured to play for the University of Edinburgh’s St Andrew’s Day celebration at St Cecilia’s Hall. One of the perks was being allowed to use historic instruments from the collection, and one of the violins I chose is this beastie without ribs, affectionately known as the pancake fiddle.

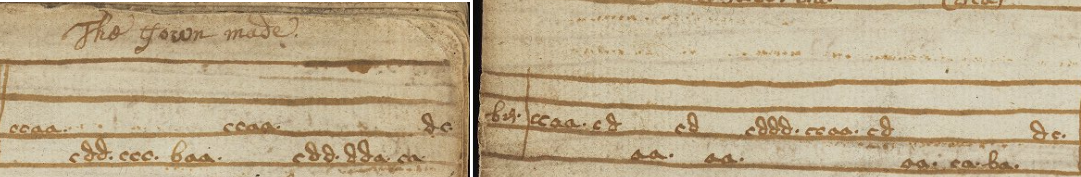

Much effort has been put into figuring out when and why it was made, and the best answers I’ve gotten so far are ‘perhaps 1550’ and ‘we’re not sure’. Regardless of its original purpose, it made sense in my head to treat it like a Renaissance violin, use a reproduction Renaissance-style bow (made of yew), play it on the arm instead of the shoulder, and play a very early tune in a Renaissancey way. Tune-shopping led me to the Guthrie Manuscript of ca. 1680, now held by the University of Edinburgh, and in perusing Aaron McGregor’s transcriptions of it I landed on a tune that’s common to this day: ‘Let Me In This Ae Nicht’, called ‘The gown made’ in the manuscript and also known as ‘The Gown Made New’ or ‘I Would Hae My Gown Made’.

The Guthrie MS is in tablature: from top to bottom the lines represent the G, D, A, and E strings of the violin and

letters on the line represent open strings (a) and then the first through fourth fingers (b through e). So a naive

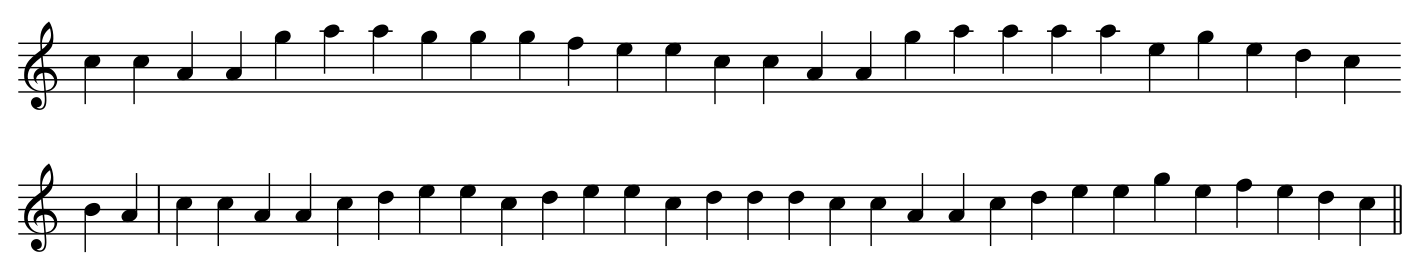

transcription results in:

Which Aaron sensibly turned into the following in his thesis:

That’s all well and good, but a 16-bar tune by itself isn’t much of a concert piece, so I made the very Renaissance move (and also the very Scottish fiddle move) of writing variations for it. Aaron has done some initial work on identifying what’s involved in 16th- and 17th-century Scottish variations, but I took the more immediately-expedient approach of Just Making It Up™ while leaning on my past experience doing three things: 1) playing many sets of Renaissance variations (especially from England and Italy) with a professional band 2) playing many sets of 18th-century Scottish variations in my own fiddle band 3) improvising variations at length for concerts and dances.

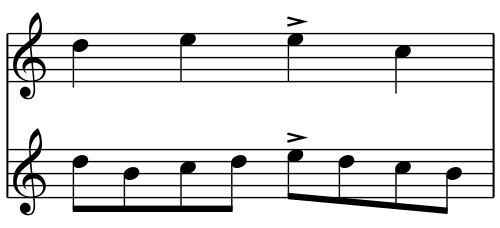

So I more or less improvised with pen in hand to come up with a first set of variations. First I made some of the notes faster while still very much keeping the shape of the melody:

Keeping the minims in the A part (the high A, G, and E in bars 2-4) helps remind the listeners that it’s a variation and not a new tune. And in the second and third bar of the B part of the original tune I see the first two crotchets as preparing the way for an emphasised third crotchet on beat 2. I captured that feeling in the variation (original and variation pictured below) by having a scale running up to the second beat and ensuring the E that lands on the second beat was the highest note of the bar.

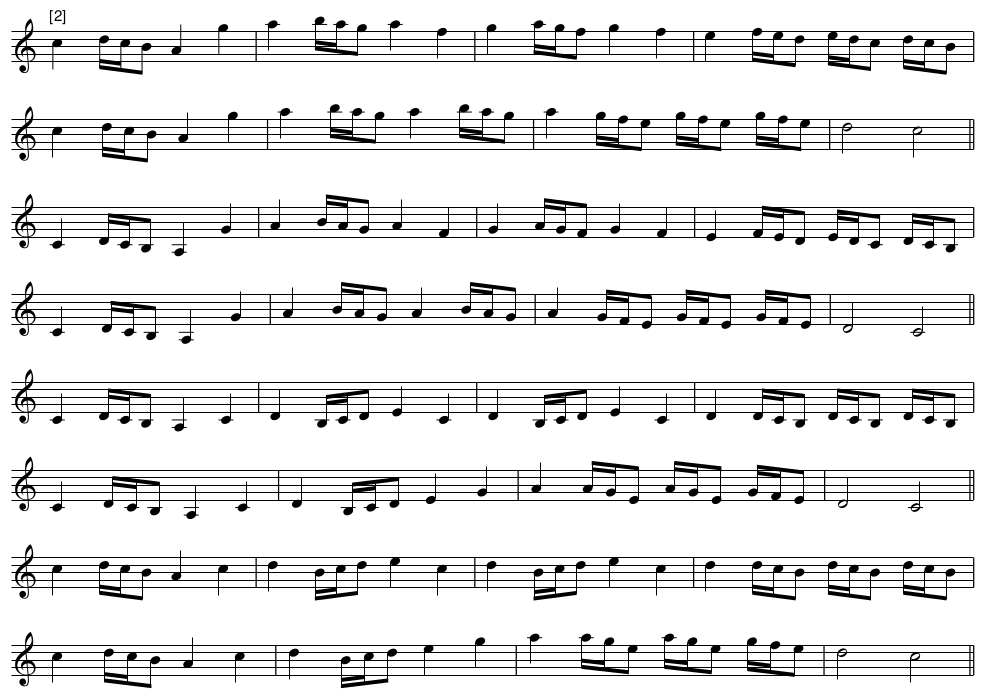

This type of variation is often called ‘divisions’ since it divides the base notes into smaller rhythmic values. If you think of the first variation as dividing crotchets in two (making quavers), you can think of the next variation as dividing crotchets into three. Rather than playing straight triplets, though, I thought it’d be more swashbuckling to accelerate into each triplet:

By this point the audience has the melody firmly in their head, so I thought it was time to do away with the ‘guidepost’ notes from the original melody that I hadn’t touched up to this point. So here’s a much busier division in quavers, with bars 6 and 7 of the A part illustrating the Scottish idiom of playing a scale figure interleaved with a pedal note.

Having thoroughly pelted the audience with notes by this point, it seemed time to be Interesting in some other way and give everyone’s ears a chance to recover with some longer note values. There are a number of things to play with, and I chose two at once: pitch and beat structure. I dropped everything down an octave and made it syncopated:

The long notes mean that doing divisions by four (semiquavers) afterwards will sound even more dashing by contrast:

In performance I’ve thought of the story so far as having a number of affects: a wistful yearning in the ground tune, a more pleading first variation, the alert variation in triplets, a flowing variation in running quavers, a gutsy syncopated variation in the lower octave, and a puckeringly poised fifth variation. But nothing so far seemed properly dancey or groove-y, so it seemed right to finish out the variations by throwing away most of the melody and just having a proper rager. Note the 3+3+2 rhythm in the B part.

That’s it for the variations, but in performance I like to repeat the base tune again.

So this was the first pass at basically-improvising a set. On playing it, I found a few problems:

-

It felt a little too long.

-

It used the upper range of the violin a lot.

-

At a performance tempo I was hit-or-miss with the semiquavers and was afraid that I’d either slow down the rest of it too much to be able to play the semiquavers or play everything at a good tempo and then choke on the fast notes.

Numbers 1 and 3 were easily solved by cutting variation #5. For #2, it seemed nice to play around with the octave in variation #2. If you consider the original variation as AABB and read the prime mark (‘) as ‘down an octave’, I changed it to AA’ B’B:

There are bigger tricks to try, such as changing metre entirely (say, to 6/8), having a dramatic tempo change, or using more elaborate violinistic tricks like upper position work or a double stop section (in performance I did improvise some double stops at the end). But I didn’t want to risk overcomplicating it and decided to stop there.

So…that was it! You can get a PDF of the finished sheet music here, and here’s a recording of (most of) the performance from St Andrew’s Day: