The Driven Bow?

16 Mar 2022

Perhaps the first thing I learned in my first ever Scottish fiddle lesson was the so-called ‘arrow stroke’ or ‘up-driven bow’, and as I continued to study it became clear that there’s a very strong tradition, especially among Northeast-style players, of using it in strathspeys and claiming it was invented by Niel Gow. There isn’t a primary source tying it to Gow, but there is at least one thing worth mentioning…

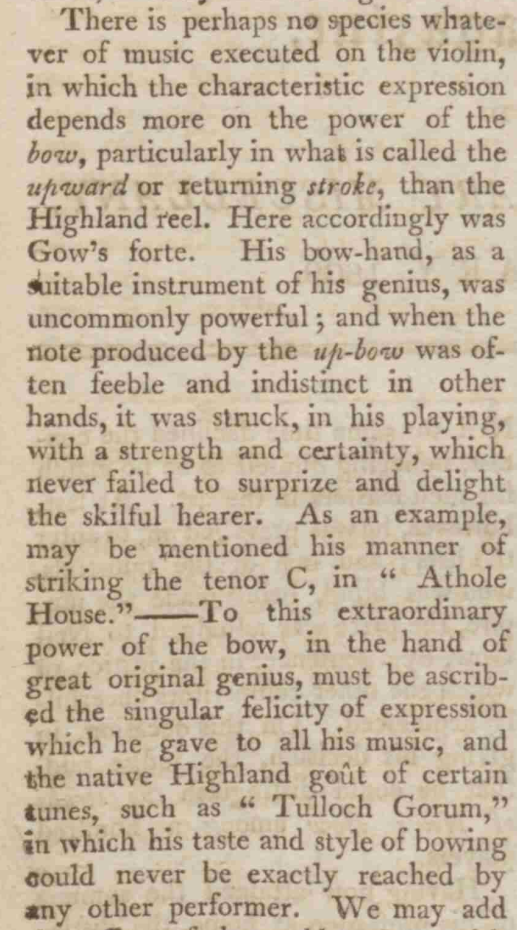

Gow’s biography, printed in the January, 1809 issue of The Scots Magazine and Edinburgh Literary miscellany (nearly two years after his death), is likely the main source for bowing stories about Gow. First it tells of a fiddle competition that Niel competed in as a teenager, where he won and the blind judge ‘said that he could distinguish the stroke of Neil’s Bow among a hundred players’ (emphasis in the original).

Later on we learn about the ‘upward or returning stroke [which] was Gow’s forte. His bow-hand […] was uncommonly powerful; and when the note produced by the up-bow was often feeble and indistinct in other hands, it was struck, in his playing, with a strength and certainty, which never failed to surprize and delight the skilful hearer.’

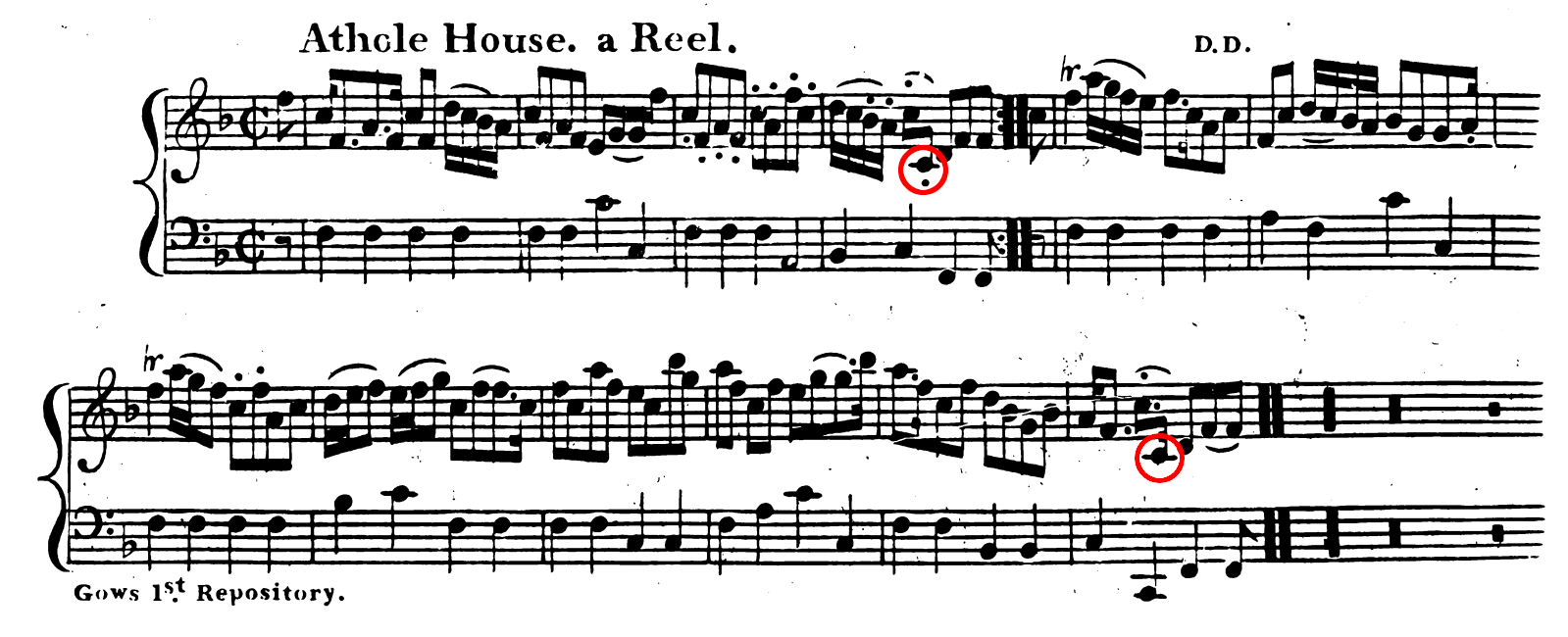

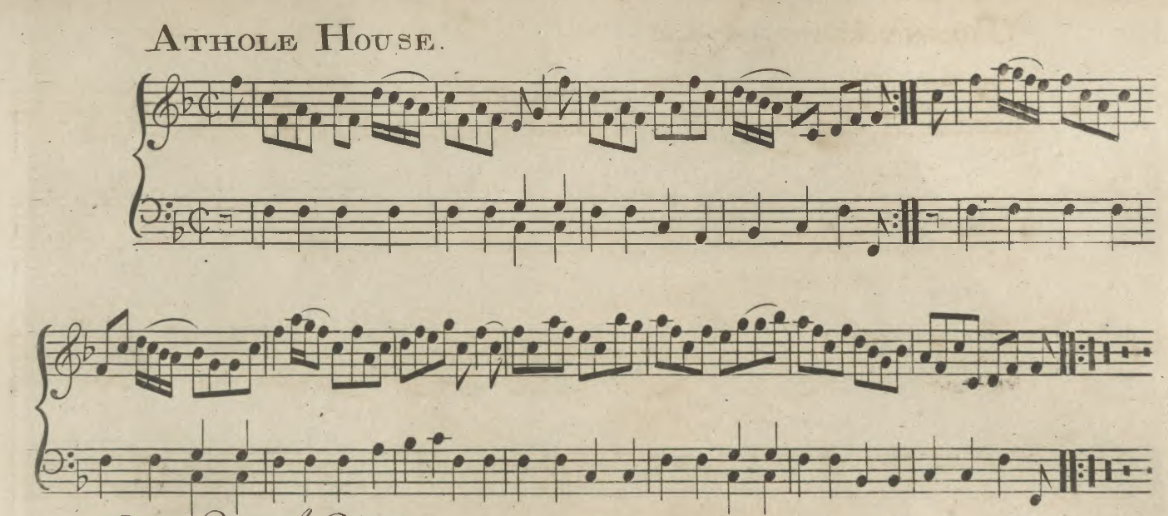

An example: Athole House

The most interesting part is the specific mention of Gow’s ‘manner of striking the tenor C, in “Athole House.”’ Here’s the tune as published in the Gows’ Complete Repository and as first published by its composer, Daniel Dow, in his Twenty Minuets and Sixteen Reels or Country Dances.

Assuming the slurs are correct and the C is played up-bow as described, that means the last bar is played:

To avoid a very awkward string crossing it makes sense to lift the bow after the high C, which is supported by the staccato dot on it. That also means the bow can come down hard on the low C: ‘strength and certainty’ indeed! The notated rhythm is also helpful; a little extra time on the high C gives the player more of a chance to lift the bow, and the low C being a semiquaver instead of a quaver if anything accents it more. The extra accent (the low C) introducing the open D is a nice rhythmic effect to end the phrase, and indeed I think the C-to-D gesture is the point to the whole exercise. It’s just not half as exciting with a weak C; it makes the tune sound a little too square.

The end of the A part isn’t quite as neat, but still works fine:

Mechanically it’s quite simlar to the above. I imagine slurring the final two Fs together is up to the player’s discretion in the moment, and I believe the slurred staccato indication on the semiquavers is not a call for portato, but rather an indication that it can be played as four slurred notes or two slurred and two separate notes. Both work nicely.

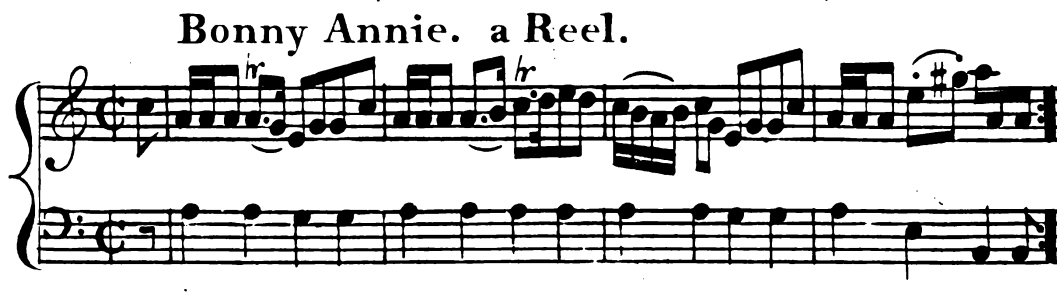

In general I think the accented up-bow works nicely in all sorts of places. Earlier in the same volume of the Repository we find Bonny Annie. The E-G# figure in the last bar of the A part is very reminiscent of the C-C figure from Athole House (substitute “G#” for “tenor C”). It also lends itself to having accented up bows used on the Cs that end the first and third bars.

Terminology?

The modern driven bow refers to a down-up-up-up (three ups) figure, and it’s worth explicitly noting that the Gow examples above use only two ups. Moving forward by a century, William Honeyman talks about a ‘catching of the driven note’ and proposes some schemes to drive the one note generally involving a two-note slur. It’s very similar but not identical to the Gow scheme above. Skinner’s Guide to Bowing does not describe driven notes, but explains the modern slur-three in great detail and calls it ‘the loop’.

I think the glory of writing a blogpost instead of a proper article is that you can end without a conclusion, so I’ll leave it there to be revisited in more detail later. Happy fiddling!